Gyro Monorail on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The gyro monorail, gyroscopic monorail, gyro-stabilized monorail, or

The gyro monorail, gyroscopic monorail, gyro-stabilized monorail, or

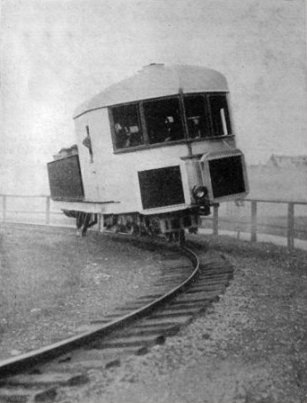

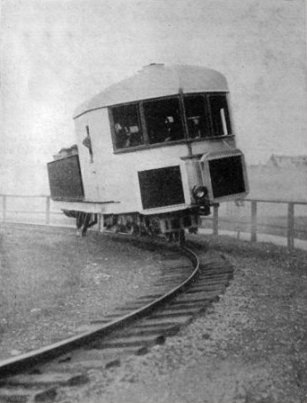

The image in the leader section depicts the 22

The image in the leader section depicts the 22

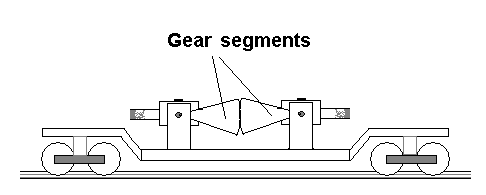

Scherl's machine, also a full size vehicle, was somewhat smaller than Brennan's, with a length of only 17 ft (5.2m). It could accommodate four passengers on a pair of transverse bench seats. The gyros were located under the seats, and had vertical axes, while Brennan used a pair of horizontal axis gyros. The

Scherl's machine, also a full size vehicle, was somewhat smaller than Brennan's, with a length of only 17 ft (5.2m). It could accommodate four passengers on a pair of transverse bench seats. The gyros were located under the seats, and had vertical axes, while Brennan used a pair of horizontal axis gyros. The

Машина незадолго до испытаний.jpg, Schilowsky's gyrocar

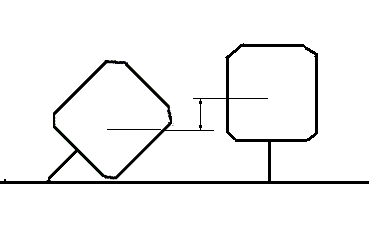

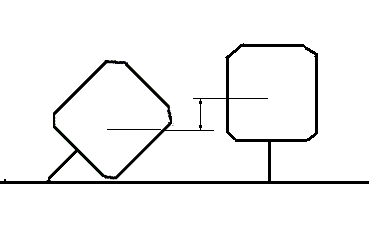

A spinning wheel is mounted in a

A spinning wheel is mounted in a

Shilovsky claimed to have difficulty ensuring stability with double-gyro systems, although the reason why this should be so is not clear. His solution was to vary the control loop parameters with turn rate, to maintain similar response in turns of either direction.

Offset loads similarly cause the vehicle to lean until the centre of gravity lies above the support point. Side winds cause the vehicle to tilt into them, to resist them with a component of weight. These contact forces are likely to cause more discomfort than cornering forces, because they will result in net side forces being experienced on board.

The contact side forces result in a gimbal deflection

Shilovsky claimed to have difficulty ensuring stability with double-gyro systems, although the reason why this should be so is not clear. His solution was to vary the control loop parameters with turn rate, to maintain similar response in turns of either direction.

Offset loads similarly cause the vehicle to lean until the centre of gravity lies above the support point. Side winds cause the vehicle to tilt into them, to resist them with a component of weight. These contact forces are likely to cause more discomfort than cornering forces, because they will result in net side forces being experienced on board.

The contact side forces result in a gimbal deflection

*Shilovsky claimed his designs were actually lighter than the equivalent duo-rail vehicles. The gyro mass, according to Brennan, accounts for 3–5% of the vehicle weight, which is comparable to the bogie weight saved in using a single track design.

*Shilovsky claimed his designs were actually lighter than the equivalent duo-rail vehicles. The gyro mass, according to Brennan, accounts for 3–5% of the vehicle weight, which is comparable to the bogie weight saved in using a single track design.

Considering a vehicle negotiating a horizontal curve, the most serious problems arise if the gyro axis is vertical. There is a component of turn rate acting about the gimbal pivot, so that an additional gyroscopic moment is introduced into the roll equation:

:::

This displaces the roll from the correct bank angle for the turn, but more seriously, changes the constant term in the characteristic equation to:

:::

Evidently, if the turn rate exceeds a critical value:

::

The balancing loop will become unstable.

However, an identical gyro spinning in the opposite sense will cancel the roll torque which is causing the instability, and if it is forced to precess in the opposite direction to the first gyro will produce a control torque in the same direction.

In 1972, the Canadian Government's Division of Mechanical Engineering rejected a monorail proposal largely on the basis of this problem. Their analysis was correct, but restricted in scope to single vertical axis gyro systems, and not universal.

Considering a vehicle negotiating a horizontal curve, the most serious problems arise if the gyro axis is vertical. There is a component of turn rate acting about the gimbal pivot, so that an additional gyroscopic moment is introduced into the roll equation:

:::

This displaces the roll from the correct bank angle for the turn, but more seriously, changes the constant term in the characteristic equation to:

:::

Evidently, if the turn rate exceeds a critical value:

::

The balancing loop will become unstable.

However, an identical gyro spinning in the opposite sense will cancel the roll torque which is causing the instability, and if it is forced to precess in the opposite direction to the first gyro will produce a control torque in the same direction.

In 1972, the Canadian Government's Division of Mechanical Engineering rejected a monorail proposal largely on the basis of this problem. Their analysis was correct, but restricted in scope to single vertical axis gyro systems, and not universal.

Monorail Society Special Feature on Swinney's monorail

Gyroscope Railroad

{{DEFAULTSORT:Gyro Monorail Monorails Experimental and prototype gyroscopic vehicles Irish inventions Australian inventions

The gyro monorail, gyroscopic monorail, gyro-stabilized monorail, or

The gyro monorail, gyroscopic monorail, gyro-stabilized monorail, or gyrocar

A gyrocar is a two-wheeled automobile. The difference between a bicycle or motorcycle and a gyrocar is that in a bike, dynamic balance is provided by the rider, and in some cases by the geometry and mass distribution of the bike itself, and the g ...

are terms for a single rail land vehicle

A vehicle (from la, vehiculum) is a machine that transports people or cargo. Vehicles include wagons, bicycles, motor vehicles (motorcycles, cars, trucks, buses, mobility scooters for disabled people), railed vehicles (trains, trams), wate ...

that uses the gyroscopic

A gyroscope (from Ancient Greek γῦρος ''gŷros'', "round" and σκοπέω ''skopéō'', "to look") is a device used for measuring or maintaining orientation and angular velocity. It is a spinning wheel or disc in which the axis of rotat ...

action of a spinning

Spin or spinning most often refers to:

* Spinning (textiles), the creation of yarn or thread by twisting fibers together, traditionally by hand spinning

* Spin, the rotation of an object around a central axis

* Spin (propaganda), an intentionally b ...

wheel to overcome the inherent instability

In numerous fields of study, the component of instability within a system is generally characterized by some of the outputs or internal states growing without bounds. Not all systems that are not stable are unstable; systems can also be mar ...

of balancing on top of a single rail.

The monorail is associated with the names Louis Brennan

Louis Brennan (28 January 1852 – 17 January 1932) was an Irish-Australian mechanical engineer and inventor.

Biography

Brennan was born in Castlebar, Ireland, and moved to Melbourne, Australia in 1861 with his parents. He started his caree ...

, August Scherl

August Scherl (24 July 1849 – 18 April 1921) was a German newspaper magnate.

Life

August Hugo Friedrich Scherl founded a newspaper and publishing concern on 1 October 1883, which from 1900 carried the name August Scherl Verlag. He wa ...

and Pyotr Shilovsky

Pyotr Petrovich Schilovsky (russian: Пётр Петрович Шиловский) (September 22, 1872 – June 30, 1955 in Herefordshire) was a Russian count, jurist, statesman, and governor of Kostroma from 1910 to 1912 and of Olonets Governorate ...

, who each built full-scale working prototype

A prototype is an early sample, model, or release of a product built to test a concept or process. It is a term used in a variety of contexts, including semantics, design, electronics, and Software prototyping, software programming. A prototyp ...

s during the early part of the twentieth century. A version was developed by Ernest F. Swinney, Harry Ferreira and Louis E. Swinney in the US in 1962.

The gyro monorail was never developed beyond the prototype stage.

The principal advantage of the monorail cited by Shilovsky is the suppression of hunting oscillation

Hunting oscillation is a self-oscillation, usually unwanted, about an equilibrium. The expression came into use in the 19th century and describes how a system "hunts" for equilibrium. The expression is used to describe phenomena in such diverse ...

, a speed limitation encountered by conventional railways at the time. Also, sharper turns are possible compared to the 7 km radius of turn typical of modern high-speed trains such as the TGV

The TGV (french: Train à Grande Vitesse, "high-speed train"; previously french: TurboTrain à Grande Vitesse, label=none) is France's intercity high-speed rail service, operated by SNCF. SNCF worked on a high-speed rail network from 1966 to 19 ...

, because the vehicle will bank automatically on bends, like an aircraft, so that no lateral centrifugal acceleration

In Newtonian mechanics, the centrifugal force is an inertial force (also called a "fictitious" or "pseudo" force) that appears to act on all objects when viewed in a rotating frame of reference. It is directed away from an axis which is paralle ...

is experienced on board.

A major drawback is that many cars – including passenger and freight cars, not just the locomotive – would require a powered gyroscope to stay upright.

Unlike other means of maintaining balance, such as lateral shifting of the centre of gravity

In physics, the center of mass of a distribution of mass in space (sometimes referred to as the balance point) is the unique point where the weighted relative position of the distributed mass sums to zero. This is the point to which a force may ...

or the use of reaction wheels

A reaction wheel (RW) is used primarily by spacecraft for three-axis attitude control, and does not require rockets or external applicators of torque. They provide a high pointing accuracy, and are particularly useful when the spacecraft must be ...

, the gyroscopic balancing system is statically stable, so that the control system serves only to impart dynamic stability. The active part of the balancing system is therefore more accurately described as a roll damper.

Historical background

Brennan's monorail

The image in the leader section depicts the 22

The image in the leader section depicts the 22 tonne

The tonne ( or ; symbol: t) is a unit of mass equal to 1000 kilograms. It is a non-SI unit accepted for use with SI. It is also referred to as a metric ton to distinguish it from the non-metric units of the short ton ( United State ...

(unladen weight) prototype vehicle developed by Louis Philip Brennan. Brennan filed his first monorail patent in 1903.

His first demonstration model was just a box containing the balancing system. However, this was sufficient for the Army Council to recommend a sum of for the development of a full-size vehicle. This was vetoed by their Financial Department. However, the Army found from various sources to fund Brennan's work.

Within this budget Brennan produced a larger model, , kept in balance by two diameter gyroscope rotors. This model is still in existence in the London Science Museum

The Science Museum is a major museum on Exhibition Road in South Kensington, London. It was founded in 1857 and is one of the city's major tourist attractions, attracting 3.3 million visitors annually in 2019.

Like other publicly funded ...

. The track for the vehicle was laid in the grounds of Brennan's house in Gillingham, Kent

Gillingham ( ) is a large town in the unitary authority area of Medway in the ceremonial county of Kent, England. The town forms a conurbation with neighbouring towns Chatham, Rochester, Strood and Rainham. It is also the largest town in the ...

. It consisted of ordinary gas piping laid on wooden sleepers, with a wire rope bridge, sharp corners and slope

In mathematics, the slope or gradient of a line is a number that describes both the ''direction'' and the ''steepness'' of the line. Slope is often denoted by the letter ''m''; there is no clear answer to the question why the letter ''m'' is use ...

s up to one in five. Brennan demonstrated his model in a lecture to the Royal Society in 1907 when it was shown running back and forth "on a taught and slender wire" "under the perfect control of the inventor".

Brennan's reduced scale railway largely vindicated the War Department War Department may refer to:

* War Department (United Kingdom)

* United States Department of War (1789–1947)

See also

* War Office, a former department of the British Government

* Ministry of defence

* Ministry of War

* Ministry of Defence

* D ...

's initial enthusiasm. However, the election in 1906 of a Liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

government, with policies of financial retrenchment, effectively stopped the funding from the Army. However, the India Office

The India Office was a British government department established in London in 1858 to oversee the administration, through a Viceroy and other officials, of the Provinces of India. These territories comprised most of the modern-day nations of I ...

voted an advance of in 1907 to develop the monorail for the North West Frontier region, and a further was advanced by the Durbar

Durbar can refer to:

* Conference of Rulers, a council of Malay monarchs

* Durbar festival, a yearly festival in several towns of Nigeria

* Durbar floor plate, a hot-rolled structural steel that has been designed to give excellent slip resistance ...

of Kashmir

Kashmir () is the northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent. Until the mid-19th century, the term "Kashmir" denoted only the Kashmir Valley between the Great Himalayas and the Pir Panjal Range. Today, the term encompas ...

in 1908. This money was almost spent by January 1909, when the India Office advanced a further .

On 15 October 1909, the railcar

A railcar (not to be confused with a railway car) is a self-propelled railway vehicle designed to transport passengers. The term "railcar" is usually used in reference to a train consisting of a single coach (carriage, car), with a drive ...

ran under its own power for the first time, carrying 32 people around the factory. The vehicle was , and with a petrol engine

A petrol engine (gasoline engine in American English) is an internal combustion engine designed to run on petrol (gasoline). Petrol engines can often be adapted to also run on fuels such as liquefied petroleum gas and ethanol blends (such as ''E ...

, had a speed

In everyday use and in kinematics, the speed (commonly referred to as ''v'') of an object is the magnitude of the change of its position over time or the magnitude of the change of its position per unit of time; it is thus a scalar quanti ...

of . The transmission

Transmission may refer to:

Medicine, science and technology

* Power transmission

** Electric power transmission

** Propulsion transmission, technology allowing controlled application of power

*** Automatic transmission

*** Manual transmission

*** ...

was electric

Electricity is the set of physical phenomena associated with the presence and motion of matter that has a property of electric charge. Electricity is related to magnetism, both being part of the phenomenon of electromagnetism, as described by ...

, with the petrol engine driving a generator

Generator may refer to:

* Signal generator, electronic devices that generate repeating or non-repeating electronic signals

* Electric generator, a device that converts mechanical energy to electrical energy.

* Generator (circuit theory), an eleme ...

, and electric motors

An electric motor is an electrical machine that converts electrical energy into mechanical energy. Most electric motors operate through the interaction between the motor's magnetic field and electric current in a wire winding to generate force ...

located on both bogie

A bogie ( ) (in some senses called a truck in North American English) is a chassis or framework that carries a wheelset, attached to a vehicle—a modular subassembly of wheels and axles. Bogies take various forms in various modes of transp ...

s. This generator also supplied power to the gyro motors and the air compressor

An air compressor is a pneumatic device that converts power (using an electric motor, diesel or gasoline engine, etc.) into potential energy stored in pressurized air (i.e., compressed air). By one of several methods, an air compressor forces ...

. The balancing system used a pneumatic

Pneumatics (from Greek ‘wind, breath’) is a branch of engineering that makes use of gas or pressurized air.

Pneumatic systems used in Industrial sector, industry are commonly powered by compressed air or compressed inert gases. A central ...

servo

Servo may refer to:

Mechanisms

* Servomechanism, or servo, a device used to provide control of a desired operation through the use of feedback

** AI servo, an autofocus mode

** Electrohydraulic servo valve, an electrically operated valve that c ...

, rather than the friction wheels used in the earlier model.

The gyros were located in the cab, although Brennan planned to re-site them under the floor of the vehicle before displaying the vehicle in public, but the unveiling of Scherl's machine forced him to bring forward the first public demonstration to 10 November 1909. There was insufficient time to re-position the gyros before the monorail's public debut.

The real public debut for Brennan's monorail was the Japan-British Exhibition at the White City White City may refer to:

Places Australia

* White City, Perth, an amusement park on the Perth foreshore

* White City railway station, a former railway station

* White City Stadium (Sydney), a tennis centre in Sydney

* White City FC, a football clu ...

, London in 1910. The monorail car carried 50 passengers at a time around a circular track at . Passengers included Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

, who showed considerable enthusiasm. Interest was such that children's clockwork monorail toys, single-wheeled and gyro-stabilised, were produced in England and Germany. Although a viable means of transport, the monorail failed to attract further investment. Of the two vehicles built, one was sold as scrap, and the other was used as a park shelter until 1930.

Scherl's car

Just as Brennan completed testing his vehicle,August Scherl

August Scherl (24 July 1849 – 18 April 1921) was a German newspaper magnate.

Life

August Hugo Friedrich Scherl founded a newspaper and publishing concern on 1 October 1883, which from 1900 carried the name August Scherl Verlag. He wa ...

, a German publisher

Publishing is the activity of making information, literature, music, software and other content available to the public for sale or for free. Traditionally, the term refers to the creation and distribution of printed works, such as books, newsp ...

and philanthropist

Philanthropy is a form of altruism that consists of "private initiatives, for the Public good (economics), public good, focusing on quality of life". Philanthropy contrasts with business initiatives, which are private initiatives for private goo ...

, announced a public demonstration of the gyro monorail which he had developed in Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

. The demonstration was to take place on Wednesday 10 November 1909 at the Berlin Zoological Gardens.

servomechanism

In control engineering a servomechanism, usually shortened to servo, is an automatic device that uses error-sensing negative feedback to correct the action of a mechanism. On displacement-controlled applications, it usually includes a built-in ...

was hydraulic

Hydraulics (from Greek: Υδραυλική) is a technology and applied science using engineering, chemistry, and other sciences involving the mechanical properties and use of liquids. At a very basic level, hydraulics is the liquid counter ...

, and propulsion

Propulsion is the generation of force by any combination of pushing or pulling to modify the translational motion of an object, which is typically a rigid body (or an articulated rigid body) but may also concern a fluid. The term is derived from ...

electric. Strictly speaking, August Scherl merely provided the financial backing. The righting mechanism was invented by Paul Fröhlich, and the car designed by Emil Falcke.

Although well received and performing perfectly during its public demonstrations, the car failed to attract significant financial support, and Scherl wrote off his investment in it.

Shilovsky's work

Following the failure of Brennan and Scherl to attract the necessary investment, the practical development of the gyro-monorail after 1910 continued with the work ofPyotr Shilovsky

Pyotr Petrovich Schilovsky (russian: Пётр Петрович Шиловский) (September 22, 1872 – June 30, 1955 in Herefordshire) was a Russian count, jurist, statesman, and governor of Kostroma from 1910 to 1912 and of Olonets Governorate ...

, a Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

n aristocrat

The aristocracy is historically associated with "hereditary" or "ruling" social class. In many states, the aristocracy included the upper class of people (aristocrats) with hereditary rank and titles. In some, such as ancient Greece, ancient Ro ...

residing in London. His balancing system was based on slightly different principles to those of Brennan and Scherl, and permitted the use of a smaller, more slowly spinning gyroscope. After developing a model gyro monorail in 1911, he designed a gyrocar

A gyrocar is a two-wheeled automobile. The difference between a bicycle or motorcycle and a gyrocar is that in a bike, dynamic balance is provided by the rider, and in some cases by the geometry and mass distribution of the bike itself, and the g ...

which was built by Wolseley Motors Limited and tested on the streets of London in 1913. Since it used a single gyro, rather than the counter-rotating pair favoured by Brennan and Scherl, it exhibited asymmetry

Asymmetry is the absence of, or a violation of, symmetry (the property of an object being invariant to a transformation, such as reflection). Symmetry is an important property of both physical and abstract systems and it may be displayed in pre ...

in its behaviour, and became unstable

In numerous fields of study, the component of instability within a system is generally characterized by some of the outputs or internal states growing without bounds. Not all systems that are not stable are unstable; systems can also be mar ...

during sharp left hand turns. It attracted interest but no serious funding.

Post-World War I developments

In 1922, theSoviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

government began construction of a Shilovsky monorail between Leningrad

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

and Tsarskoe Selo

Tsarskoye Selo ( rus, Ца́рское Село́, p=ˈtsarskəɪ sʲɪˈlo, a=Ru_Tsarskoye_Selo.ogg, "Tsar's Village") was the town containing a former residence of the Russian imperial family and visiting nobility, located south from the c ...

, but funds ran out shortly after the project was begun.

In 1929, at the age of 74, Brennan also developed a gyrocar. This was turned down by a consortium of Austin

Austin is the capital city of the U.S. state of Texas, as well as the seat and largest city of Travis County, with portions extending into Hays and Williamson counties. Incorporated on December 27, 1839, it is the 11th-most-populous city ...

/Morris

Morris may refer to:

Places

Australia

*St Morris, South Australia, place in South Australia

Canada

* Morris Township, Ontario, now part of the municipality of Morris-Turnberry

* Rural Municipality of Morris, Manitoba

** Morris, Manitob ...

/Rover

Rover may refer to:

People

* Constance Rover (1910–2005), English historian

* Jolanda de Rover (born 1963), Dutch swimmer

* Rover Thomas (c. 1920–1998), Indigenous Australian artist

Places

* Rover, Arkansas, US

* Rover, Missouri, US

...

, on the basis that they could sell all the conventional cars they built.

21st century: Monocab

In October 2022 theTechnische Hochschule OWL

The Technische Hochschule Ostwestfalen-Lippe (abbreviated: TH OWL, English: OWL University of Applied Sciences and Arts) is a state tech university in the Ostwestfalen-Lippe area in Lemgo, which is part of North Rhine-Westphalia. Additional cam ...

, the Bielefeld University of Applied Sciences, the Fraunhofer-Institut für Optronik, Systemtechnik und Bildauswertung and the Landeseisenbahn Lippe e. V. presented a gyro-stabilized monorail according to Brennan on a section of the Extertal railway in Germany.

The system called ''Monocab'' is meant to permit bi-directional service on a single track since the vehicles use only one rail. The cabins that shall operate autonomously on-demand are designed accordingly narrow.

In September 2020 Monocab was funded from the European Regional Development Fund

The European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) is one of the European Structural and Investment Funds allocated by the European Union. Its purpose is to transfer money from richer regions (not countries), and invest it in the infrastructure and se ...

and by the state of North Rhine-Westphalia

North Rhine-Westphalia (german: Nordrhein-Westfalen, ; li, Noordrien-Wesfale ; nds, Noordrhien-Westfalen; ksh, Noodrhing-Wäßßfaale), commonly shortened to NRW (), is a States of Germany, state (''Land'') in Western Germany. With more tha ...

with 3.6 million euros combined.

Principles of operation

Basic idea

The vehicle runs on a single conventional rail, so that without the balancing system it would topple over. A spinning wheel is mounted in a

A spinning wheel is mounted in a gimbal

A gimbal is a pivoted support that permits rotation of an object about an axis. A set of three gimbals, one mounted on the other with orthogonal pivot axes, may be used to allow an object mounted on the innermost gimbal to remain independent of ...

frame whose axis of rotation (the precession axis) is perpendicular

In elementary geometry, two geometric objects are perpendicular if they intersect at a right angle (90 degrees or π/2 radians). The condition of perpendicularity may be represented graphically using the ''perpendicular symbol'', ⟂. It can ...

to the spin axis. The assembly is mounted on the vehicle chassis

A chassis (, ; plural ''chassis'' from French châssis ) is the load-bearing framework of an artificial object, which structurally supports the object in its construction and function. An example of a chassis is a vehicle frame, the underpart ...

such that, at equilibrium, the spin axis, precession axis and vehicle roll axis are mutually perpendicular.

Forcing the gimbal to rotate causes the wheel to precess resulting in gyroscopic torque

In physics and mechanics, torque is the rotational equivalent of linear force. It is also referred to as the moment of force (also abbreviated to moment). It represents the capability of a force to produce change in the rotational motion of th ...

s about the roll axis, so that the mechanism has the potential to right the vehicle when tilted from the vertical

Vertical is a geometric term of location which may refer to:

* Vertical direction, the direction aligned with the direction of the force of gravity, up or down

* Vertical (angles), a pair of angles opposite each other, formed by two intersecting s ...

. The wheel shows a tendency to align its spin axis with the axis of rotation (the gimbal axis), and it is this action which rotates the entire vehicle about its roll axis.

Ideally, the mechanism applying control torques to the gimbal ought to be passive

Passive may refer to:

* Passive voice, a grammatical voice common in many languages, see also Pseudopassive

* Passive language, a language from which an interpreter works

* Passivity (behavior), the condition of submitting to the influence of on ...

(an arrangement of spring

Spring(s) may refer to:

Common uses

* Spring (season)

Spring, also known as springtime, is one of the four temperate seasons, succeeding winter and preceding summer. There are various technical definitions of spring, but local usage of ...

s, damper

A damper is a device that deadens, restrains, or depresses. It may refer to:

Music

* Damper pedal, a device that mutes musical tones, particularly in stringed instruments

* A mute for various brass instruments

Structure

* Damper (flow), a mechan ...

s and lever

A lever is a simple machine consisting of a beam or rigid rod pivoted at a fixed hinge, or ''fulcrum''. A lever is a rigid body capable of rotating on a point on itself. On the basis of the locations of fulcrum, load and effort, the lever is div ...

s), but the fundamental nature of the problem indicates that this would be impossible. The equilibrium position is with the vehicle upright, so that any disturbance from this position reduces the height of the centre of gravity

In physics, the center of mass of a distribution of mass in space (sometimes referred to as the balance point) is the unique point where the weighted relative position of the distributed mass sums to zero. This is the point to which a force may ...

, lowering the potential energy

In physics, potential energy is the energy held by an object because of its position relative to other objects, stresses within itself, its electric charge, or other factors.

Common types of potential energy include the gravitational potentia ...

of the system. Whatever returns the vehicle to equilibrium must be capable of restoring this potential energy, and hence cannot consist of passive elements alone. The system must contain an active servo

Servo may refer to:

Mechanisms

* Servomechanism, or servo, a device used to provide control of a desired operation through the use of feedback

** AI servo, an autofocus mode

** Electrohydraulic servo valve, an electrically operated valve that c ...

of some kind.

Side loads

If constant side forces were resisted by gyroscopic action alone, the gimbal would rotate quickly on to the stops, and the vehicle would topple. In fact, the mechanism causes the vehicle to lean into the disturbance, resisting it with a component of weight, with the gyro near its undeflected position. Inertial side forces, arising from cornering, cause the vehicle to lean into the corner. A single gyro introduces anasymmetry

Asymmetry is the absence of, or a violation of, symmetry (the property of an object being invariant to a transformation, such as reflection). Symmetry is an important property of both physical and abstract systems and it may be displayed in pre ...

which will cause the vehicle to lean too far, or not far enough for the net force to remain in the plane of symmetry, so side forces will still be experienced on board.

In order to ensure that the vehicle bank

A bank is a financial institution that accepts deposits from the public and creates a demand deposit while simultaneously making loans. Lending activities can be directly performed by the bank or indirectly through capital markets.

Because ...

s correctly on corners, it is necessary to remove the gyroscopic torque

In physics and mechanics, torque is the rotational equivalent of linear force. It is also referred to as the moment of force (also abbreviated to moment). It represents the capability of a force to produce change in the rotational motion of th ...

arising from the vehicle rate of turn.

A free gyro keeps its orientation with respect to inertial space

In classical physics and special relativity, an inertial frame of reference (also called inertial reference frame, inertial frame, inertial space, or Galilean reference frame) is a frame of reference that is not undergoing any acceleration. ...

, and gyroscopic moments are generated by rotating it about an axis perpendicular to the spin axis. But the control system

A control system manages, commands, directs, or regulates the behavior of other devices or systems using control loops. It can range from a single home heating controller using a thermostat controlling a domestic boiler to large industrial c ...

deflects the gyro with respect to the chassis

A chassis (, ; plural ''chassis'' from French châssis ) is the load-bearing framework of an artificial object, which structurally supports the object in its construction and function. An example of a chassis is a vehicle frame, the underpart ...

, and not with respect to the fixed stars. It follows that the pitch and yaw motion of the vehicle with respect to inertial space will introduce additional unwanted, gyroscopic torques. These give rise to unsatisfactory equilibria, but more seriously, cause a loss of static stability when turning in one direction, and an increase in static stability in the opposite direction. Shilovsky encountered this problem with his road vehicle, which consequently could not make sharp left hand turns.

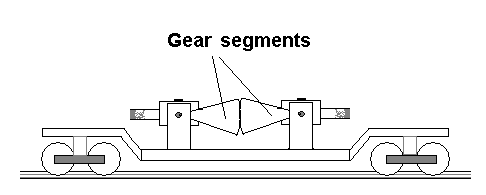

Brennan and Scherl were aware of this problem, and implemented their balancing systems with pairs of counter rotating gyros, precessing in opposite directions. With this arrangement, all motion of the vehicle with respect to inertial space causes equal and opposite torques on the two gyros, and are consequently cancelled out. With the double gyro system, the instability on bends is eliminated and the vehicle will bank to the correct angle, so that no net side force is experienced on board.

Shilovsky claimed to have difficulty ensuring stability with double-gyro systems, although the reason why this should be so is not clear. His solution was to vary the control loop parameters with turn rate, to maintain similar response in turns of either direction.

Offset loads similarly cause the vehicle to lean until the centre of gravity lies above the support point. Side winds cause the vehicle to tilt into them, to resist them with a component of weight. These contact forces are likely to cause more discomfort than cornering forces, because they will result in net side forces being experienced on board.

The contact side forces result in a gimbal deflection

Shilovsky claimed to have difficulty ensuring stability with double-gyro systems, although the reason why this should be so is not clear. His solution was to vary the control loop parameters with turn rate, to maintain similar response in turns of either direction.

Offset loads similarly cause the vehicle to lean until the centre of gravity lies above the support point. Side winds cause the vehicle to tilt into them, to resist them with a component of weight. These contact forces are likely to cause more discomfort than cornering forces, because they will result in net side forces being experienced on board.

The contact side forces result in a gimbal deflection bias

Bias is a disproportionate weight ''in favor of'' or ''against'' an idea or thing, usually in a way that is closed-minded, prejudicial, or unfair. Biases can be innate or learned. People may develop biases for or against an individual, a group, ...

in a Shilovsky loop. This may be used as an input to a slower loop to shift the centre of gravity laterally, so that the vehicle remains upright in the presence of sustained non-inertial forces. This combination of gyro and lateral cg shift is the subject of a 1962 patent. A vehicle using a gyro/lateral payload

Payload is the object or the entity which is being carried by an aircraft or launch vehicle. Sometimes payload also refers to the carrying capacity of an aircraft or launch vehicle, usually measured in terms of weight. Depending on the nature of ...

shift was built by Ernest F. Swinney, Harry Ferreira and Louis E. Swinney in the US in 1962. This system is called the Gyro-Dynamics monorail.

Potential advantages over two-rail vehicles

Shilovsky gave a number of claimed benefits including: * Reduced right-of-way problems because steeper gradients and sharper corners may be negotiated in theory. In his book, Shilovsky describes a form of on-track braking, which is feasible with a monorail, but would upset the directional stability of a conventional rail vehicle. This has the potential of much shorter stopping distances compared with conventional wheel on steel, with a corresponding reduction in safe separation between trains. The *Shilovsky claimed his designs were actually lighter than the equivalent duo-rail vehicles. The gyro mass, according to Brennan, accounts for 3–5% of the vehicle weight, which is comparable to the bogie weight saved in using a single track design.

*Shilovsky claimed his designs were actually lighter than the equivalent duo-rail vehicles. The gyro mass, according to Brennan, accounts for 3–5% of the vehicle weight, which is comparable to the bogie weight saved in using a single track design.

Turning corners

Considering a vehicle negotiating a horizontal curve, the most serious problems arise if the gyro axis is vertical. There is a component of turn rate acting about the gimbal pivot, so that an additional gyroscopic moment is introduced into the roll equation:

:::

This displaces the roll from the correct bank angle for the turn, but more seriously, changes the constant term in the characteristic equation to:

:::

Evidently, if the turn rate exceeds a critical value:

::

The balancing loop will become unstable.

However, an identical gyro spinning in the opposite sense will cancel the roll torque which is causing the instability, and if it is forced to precess in the opposite direction to the first gyro will produce a control torque in the same direction.

In 1972, the Canadian Government's Division of Mechanical Engineering rejected a monorail proposal largely on the basis of this problem. Their analysis was correct, but restricted in scope to single vertical axis gyro systems, and not universal.

Considering a vehicle negotiating a horizontal curve, the most serious problems arise if the gyro axis is vertical. There is a component of turn rate acting about the gimbal pivot, so that an additional gyroscopic moment is introduced into the roll equation:

:::

This displaces the roll from the correct bank angle for the turn, but more seriously, changes the constant term in the characteristic equation to:

:::

Evidently, if the turn rate exceeds a critical value:

::

The balancing loop will become unstable.

However, an identical gyro spinning in the opposite sense will cancel the roll torque which is causing the instability, and if it is forced to precess in the opposite direction to the first gyro will produce a control torque in the same direction.

In 1972, the Canadian Government's Division of Mechanical Engineering rejected a monorail proposal largely on the basis of this problem. Their analysis was correct, but restricted in scope to single vertical axis gyro systems, and not universal.

Maximum spin rate

Gas turbine engine

A gas turbine, also called a combustion turbine, is a type of continuous flow internal combustion engine. The main parts common to all gas turbine engines form the power-producing part (known as the gas generator or core) and are, in the directi ...

s are designed with peripheral speeds as high as , and have operated reliably on thousands of aircraft over the past 50 years. Hence, an estimate of the gyro mass for a , with cg height at , assuming a peripheral speed of half what is used in jet engine design, is a mere . Brennan's recommendation of 3–5% of the vehicle mass was therefore highly conservative.

See also

*Adhesion railway

An adhesion railway relies on adhesion traction to move the train. Adhesion traction is the friction between the drive wheels and the steel rail. The term "adhesion railway" is used only when it is necessary to distinguish adhesion railways from ...

* Bicycle and motorcycle dynamics

Bicycle and motorcycle dynamics is the science of the motion of bicycles and motorcycles and their components, due to the forces acting on them. Dynamics falls under a branch of physics known as classical mechanics. Bike motions of interest ...

* Gyrocar

A gyrocar is a two-wheeled automobile. The difference between a bicycle or motorcycle and a gyrocar is that in a bike, dynamic balance is provided by the rider, and in some cases by the geometry and mass distribution of the bike itself, and the g ...

* Segway HT

The Segway is a two-wheeled, self-balancing personal transporter invented by Dean Kamen and brought to market in 2001 as the Segway HT, subsequently as the Segway PT, and manufactured by Segway Inc. ''HT'' is an initialism for "human transpo ...

* Lit Motors

Lit Motors Inc. is a San Francisco-based company that designed conceptual two-wheeled vehicles, including a fully electric, gyroscopically stabilized vehicle.

Founded by Daniel K. Kim in 2010, Lit Motors designed concepts for two-wheeled vehicl ...

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * *External links

Monorail Society Special Feature on Swinney's monorail

Gyroscope Railroad

{{DEFAULTSORT:Gyro Monorail Monorails Experimental and prototype gyroscopic vehicles Irish inventions Australian inventions